Players in the ‘web of poetic tradition’ : interpreting self-naming in Turkish Alevi sacred and secular sung poetry

This paper was accepted for the 43rd International Council for Traditional Music World Conference held in Astana, Kazakhstan, in July 2015. Unfortunately due to unforeseen personal circumstances I was forced to abort my travel en route to Astana and never got to present the paper in person. For this reason I am posting it here. The paper aims to provide a concise overview of my research interests. A PDF version of the paper can be found here: Koerbin_2015_ICTM_paper

Paul Koerbin (Copyright 2015)

“I am Pir Sultan Abdal, here in the world

Is there anything deficient in my word?

Anything lacking in my very self

I came to stand right before you!”

Here is an arresting voice to encounter in a traditional song. How meaning is experienced through such expression of the lyric persona in Alevi sung poetry has long interested me and is the subject of my research.

THESIS

So, let me declare my thesis: that the mahlas – the rhetorical invoking of the poetic persona, by name, to which the song is attributed – is a device of nuance and associative force that contributes to the creative and interpretive vitality of Alevi sacred and secular sung poetry[i].

INTRODUCTORY ANECDOTE

By way of introduction I wish to briefly recount my personal encounter with Alevi songs – collectively designated by the term deyiş. In the early 1980s as a jobbing musician in the genre that would later be characterised as ‘world music’ I became interested in Turkish music while working with Turkish and Azeri musicians. To nourish my growing interest in Turkish music I sought out the Turkish video shops in Sydney and Melbourne and collected many music cassette tapes. The recordings that particularly captured my attention were those rich in Alevi song – particularly the series of Muhabbet recordings and the recordings of Arif Sağ from the mid-1980s. In sound, the songs were affecting in their deep and sober vocal sonority performed to the accompaniment of just, or primarily, the bağlama which was both assured and intricate though restrained. Most strikingly, the songs were dense in lyric content. My initial response was to the sound since without Turkish language skills at the time I did not understand the content of the words. Even Turkish friends, non-Alevis, from whom I sought help in understanding these songs, were usually baffled and unhelpful. However, as I began to teach myself Turkish and find out more about the songs I was most struck by the overt expression of the lyric persona in the form of a declared name of attribution that came as the climax of the lyric – this is the mahlas. At this time I also first encountered the plenitude of publications devoted to the most influential of lyric personas: Pir Sultan Abdal, whose presence will pervade this paper.

For me, as an aspiring performer of these songs, this presented a dilemma that I had not considered before in performing traditional music; and posed certain questions, including:

- What does it mean to perform songs that invoke attributive personas so manifestly? And,

- What are the implications for my own performance of these ‘signed’ songs?

My purpose in emphasising my personal performing experience with Alevi song as the impetus to my scholarly interest is to raise the matter of subjectivity in my encounter with, and efforts to understand, Alevi musical culture. Simply put: is my personal experience an insight; and if so how to realise such understanding?

THEORETICAL MODEL

The way forward was provided for me by Timothy Rice’s work expressed in his seminal 1987 article ‘Towards the remodelling of ethnomusicology’ and of course in his major work May it Fill Your Soul published in 1994. Rice’s proposed epistemology provides a pathway to negotiate the antinomy between the objectivity of musicology and the subjectivity of musical experience. His model makes the object of enquiry people’s actions in creating, experiencing and using music and permits the study of musical sound to be less prominent. Rice’s model involves attention to processes of historical construction (including encounters with the forms and legacies of the past); social maintenance (including the way music is sustained and altered); and individual experience, adaptation and application. Most importantly, as Rice stated, the application of this model “demands a move from description to interpretation and explanation” (Rice 1987, 480).

In looking at these processes I structured my study along the trajectory of Ricoeur’s hermeneutical arc, moving from pre-understanding, through explanation to experience. I explored pre-understandings through textual encounters with Alevi song as authored texts perpetuated through the numerous collections formed around attributed poems. This was then followed by a closer examination and explication of the deyiş form and the mahlas as a textual integer. Finally I applied interpretive methods to a range of expressive manifestations of Alevi song: on influential recordings, at the Pir Sultan Abdal festival in the village of Banaz; and reflectively in respect to my own performances in various contexts.

In pursuing my interpretive approach I have also been influenced by the work of the late John Miles Foley and his concept of immanent art in which textual integers (and musical expression indeed) constitute places of rich associative meanings. So too the work of Thomas DuBois whose typology of interpretive strategies is instructive particularly in respect to his associative axis of attribution in which, and I quote, “a song becomes meaningful by association with a composer or performer connected with the song, or narrative character mentioned in the song’s text” (DuBois 1996, 255). Such conceptualisations help us to understand the act of attribution and the response to that attribution (by creators, performers and audiences) as interpretive strategies.

ALEVILIK

Time does not permit discussion or explication here of the complex topics of Alevi identity, the definition of Alevilik or Alevi belief systems. But I should note, as significant, the historical construction of the concept of modern Alevi identity from the long established heterodox communities in Anatolia, most specifically the kızılbaş.

Two aspects of Alevilik I wish to emphasise here are authoritative lineage and the role of the aşık. Traditional Alevi communities are connected and formed around hereditary, charismatic and hierarchical lineage and authority, encapsulated as the ocak (literally hearth). This network system of ocaks functioned to maintain social structures at the community level and connect communities together through ancient lineage. Dede (elder) families assume the authority to lead the communities in ritual, spiritual and temporal matters. In recent decades social change and movement have lessened these traditional networks. However, as an esoteric oral tradition the transmission of the texts required to support those communities in ritual remains vitally important. The agent of transmission, traditionally the aşık or minstrel though more recently this has included respected popular performers, becomes a privileged creator and re-interpreter of songs both for ritual and spiritual purpose and to express the social concerns, travails and aspirations of the community. The songs themselves continue as the primary texts of cultural experience and sacred expression.

THE MAHLAS

Structurally the deyiş (songs) of Alevi tradition are characterised in part by the explicit expression of the creative persona within the lyric itself.

The lyric invokes, generally in the final stanza, the poetic voice by name – and by extension, the ostensible author. This is the mahlas, although in Turkish folk literature discourse it may also be referred to as tapşırma or takma ad. The ubiquity of this device is telling of its functional significance. It is found in secular and social Alevi song created by aşık-s on all manner of topics; and also in the most sacred of Alevi sung poetry – such as the mersiye, the miraçlama and tevhid; and the most fundamental Alevi ritual expression, the duaz-ı imam, itself an invocation by name and epithet of the sacred lineage. Yet little serious scholarly attention has been accorded the mahlas in Alevi or Turkish expressive tradition beyond the cataloguing of typologies. I would acknowledge Doğan Kaya’s work on the aşık-s of Sivas as most useful in this regard.

This is not to say that the mahlas has not had a significant role in the way Alevi sung poetry is researched and presented. However, where there has been attention to the mahlas it has been limited to – and consequently limiting in – a focus on putative historical identities and the compilation of authorial canons of texts. Most notably this is demonstrated by the exemplary case of Pir Sultan Abdal.

Interest in collecting and presenting traditional folk lyrics in a formalised way, including publication, began in the early 20th century and took off after the Turkish language reforms in the formative years of the Turkish Republic in the late 1920s. One of the first collections of Kızılbaş-Alevi lyrics was Sadettin Nüzhet Ergun’s publication in 1929 of a short monograph on Pir Sultan Abdal which included 105 nefes or deyiş. Similar monographs devoted to other poets were produced under the auspices of Mehmet Fuat Köprülüzade. This is the beginning of an impetus towards forming divan-s or collections of lyrics structured around the persona to which the lyrics are attributed by the typology of the mahlas. The earliest studies of Pir Sultan Abdal lyrics, including those by Ergun and Köprülüzade already light upon the inconsistencies of attribution noting, for example, that some lyrics may be attributed to Pir Sultan in one place and Şah Hatayi in another. Over time this has lead to a focus on percieved errors of attribution and an impetus to search for the actual identities – and by extension the eponymous creators – responsible for the lyrics. Given the well developed legends supporting the putative life of Pir Sultan – as a rebel and martyr meeting his fate on the gallows at the hands of his former disciple, later governor of Sivas named Hızır Paşa – is it not surprising that his case presents the most well developed, though not only, example of this process.

An influential work in this respect is by the Sivas folklorist İbrahim Aslanoğlu. He proposed the notion of the Pir Sultan Abdallar (Pir Sultan Abdals) identifying six separate identities. Other scholars, such as Asım Bezirci, have promoted a similar line categorising lyrics under separate identities. Turgut Koca has even proposed a distinct ‘Serezli’ Pir Sultan Abdal located in the Balkans, despite this poet’s lyric content being essentially the same as that of the corpus of lyrics associated with the Anatolian Pir Sultan. While the methods such scholars used to distinguish the lyrics include identifying supposed reference to historic events or specific locations, the lyrics are ultimately categorised under specific forms of the mahlas: e.g. Pir Sultan, Pir Sultan Abdal, Abdal Pir Sultan, Pir Sultan Haydar. And while such work is interesting and useful the conclusion that there are mutiple creators merely provides evidence of the oral tradition at play. Deconstructing and fragmenting the Pir Sultan identity is essentially an end to itself and as such works counter to and subverts an understanding of how the persona, and the mahlas naming specifically, is experienced in an essentially oral tradition.

TAKING THE MAHLAS

The act of taking or receiving a mahlas is a signal event. At its most formal it is imbued with the bestowal of sacred authority. For example, the highly active, creative and influential Alevi leader Dertli Divani – born Veli Aykut in 1962 – received the mahlas ‘Dertli’ from Emrullah Ulusoy a descendent of Hacı Bektaş Veli at the age or 16 when he demonstrated his ability to improvise deyiş. Two months later another descendent of Hacı Bektaş Veli passed through his village in southeastern Turkey and again the young Veli improvised songs after which he was given the second mahlas ‘Divani’. Not only does this example demonstrate the lines of sacred authority that may be inherited through the receiving of a mahlas but it also highlights that it is associated with the process and demonstration of creative inspiration. Dertli Divani himself later gave the mahlas ‘Vefai’ to the bağlama virtuoso and singer (and deyiş creator) Mustafa Kılçık who performs with Divani both in ritual settings and in the performance group Hasbihal[ii]. The mahlas Vefai connoting ‘loyalty’ or ‘faithfulness’ both affirming and elevating this functional relationship.

Mahlas taking is an act that can represent both transition and commitment. Ahmet Edip in a lyric writes of being freed from the world into which he was born when he became ‘Harabi’ – one form of mahlas he used. The taking and expressing of the mahlas is a transcendent process, often being reported from a dream experience. However, there remains remarkable scope for playfulness and nuance in the process. The prolific Istanbul writer and publisher Adil Ali Atalay takes the mahlas Vaktidolu – expressing the reality of his busy life. Both Harabi and Meluli used a female mahlas on occasion, challenging the notion of a simple mahlas-identity relationship. In structural terms the mahlas may appear in a variety of grammatical constructions and tenses often resulting in an ambiguous or changeable voice – from subject to object for example – making the relationship of creators, performers and audience open to interpretation.

EXPERIENCING THE MAHLAS

In keeping with the hermeneutical trajectory of my study, I suggest that we come closer to deeper insight into the nuances of attribution in reflecting upon ways we experience the mahlas in the transmission and performance of songs.

The deyiş ‘Gelin Canlar Bir Olalım’ is one that is intrinsically linked to Pir Sultan Abdal, particularly after its association as a clarion cry for the social left in the political turmoil of the 1970s in Turkey[iii]. It is perhaps the most fearsome and unequivocally revolutionary lyric attributed to Pir Sultan; yet is imbued with the spirit of the martyrdom of the Imam Husayn. Its provenance as a Pir Sultan lyric is, like many others, contestable. Some suggest the lyric originates from Aşık Sıtkı and is included in the collection published by his grandson Muhsin Gül (along with other lyrics resembling those associated with Pir Sultan). The attribution to Pir Sultan may however have originated with Aşık Ali İzzet Özkan since it first appears in print in the 1943 collection published by Boratav and Gölpınarlı. The source of the lyric is indicated as coming from Ali İzzet’s scouring of the mecmua (manuscript) of a certain Muharrem from İğdiş village in the Şarkışla region (who of course may also be the source of the attribution). As Başgöz reports, Ali İzzet was very open about passing off the poems of other poets as Pir Sultan’s. Ali İzzet himself makes the point that he didn’t do this ‘knowingly’ but where the poems were appropriate to Pir Sultan. Aşık Ali’s comments, as reported by Başgöz, are subtle and instructive: they suggests a conscious self-aware interpretive use of the material within functional and acceptable boundaries rather than a deliberately purpetrated, ‘knowing’, deception or, indeed, an inadvertant error. Eberhard, writing in the 1950s, similarly reports that a minstrel named Mustafa Kılıç (who had been a pupil of the famous Aşık Veysel) showed ‘versatility’ in taking songs composed by Veysel and others and adding a final stanza, so that he could regard them as his own. So, perhaps, meaning is more usefully pursued in the looking at the process rather than the provenance.

The aşık Mahmut Erdal reports his meeting with the renowned folksong collector associated with Turkish Radio and Television, Nida Tüfekçi, when he played him the Divriğili Turna Semahı ‘Yine dertli dertli iniliyorsun’. Tüfekçi was enthusiastic about the semah (a sacred dance song) because of its remarkable musical qualities with multiple changes in rhythm. As with many semah the lyric component of the Turna Semahı is a compound of poems by more than one poet. In Erdal’s original version this included a not particularly remarkable (and perhaps dubious) lyric with the mahlas Pir Sultan Abdal. However so as to avoid any problems in clearing this work for inclusion in the officially sanctioned ‘repertoire’ the Pir Sultan Abdal conponent was changed to include lyric content attributed to the politically innocuous poet Karacaoğlan. Given that the content of the Pir Sultan poem was itself overtly innocuous it was the associative qualities of the name Pir Sultan Abdal at a politically conflicted time (the 1970s) that prompted this change. Interestingly since that time, the force of the official repertoire has seen the changed version of the lyric retained as the standard version, even in some Alevi contexts. This suggests that even a documented corruption of a lyric may become part of a process to be played out with new meanings rather than simply being something to be corrected. New immanent understandings emerge by virtue of its continued performance in this form; for example, the quality of inclusiveness is expressed by embracing personas or associations which are not overtly Alevi, even in ritual contexts, when acceptable and meaningful to the expression of Alevi identity.

One more example of the interpretive power of the persona associated with the lyrics must suffice. The deyiş ‘Yarim İçin Ölüyorum’ by Cafer Tan was famously recorded in the early 1980s by the virtuoso Alevi performer Arif Sağ who collected the song from Aşık Nesimi Çimen the son-in-law of aşık Cafer. Nesimi, along with Sağ, was at the fateful Pir Sultan Abdal Festival in Sivas in 1993 when 37 people were killed as the result of a riot by a religious inspired mob outside the Madımak Otel on 2 July. Thirty-three of those killed were artists, minstrels, writers and others attending the festival who died when the mob set fire to the hotel, among them Nesimi Çimen, though Sağ managed to escape the conflagration. When Arif Sağ’s son Tolga Sağ performed this song at the Pir Sultan Abdal Festival in Banaz village some years later he made a slight but significant word change in the repeated refrain of the song, singing ‘yobaz’ (bigot) instead of ‘cahil’ (ignorant). At the Festival the immanent associations of this were well recognized by the largely Alevi audience who spontaneously applauded the change. In this way, Sağ’s interpretation of Cafer’s song associated Cafer, Nesimi, Pir Sultan, the events of Sivas in 1993 and its continued remembrance with remarkable and powerful textual economy. Cafer’s song – and by extension Cafer’s poetic voice – though not originally thus, became a social and political statement, at least to a knowing audience.

IN CONCLUSION

My thesis, then, is that we can extend our understanding by both our interpretive experience of the songs and by recognizing the interpretive strategies applied by creators and performers. In this way the mahlas may be understood as a concise integer within the lyric that engenders immanent-associative meanings that in turn inspire and engage interpretive and creative processes. As such, the function of the mahlas becomes more like a node, a point of reference around which ‘players in the web of poetic tradition’ – to coopt John Miles Foley’s phrase – develop their creative and interpretive associations. Understood in this way the mahlas has a function in constructing social and cultural connections, meanings and continuity rather than merely asserting the perpetuation of individual creative property.

References

Aslanoğlu, İbrahim. 1984. Pir Sultan Abdallar. Istanbul: Erman Yayınevi.

Atılgan, Halil. 1992. Kısaslı aşıklar. Şanlıurfa: S.n.

Başgöz, İlhan. 1994. Âşık Ali İzzet Özkan. 2nd ed. Istanbul: Pan Yayıncılık.

Bezirci, Asım. 1993. 1994. Pir Sultan Abdal: yaşamı, kişiliği, sanatı, bütün şiirleri. Istanbul: Evrensel Basım Yayın. Original edition, 1986.

Clarke, Gloria L. 1999. The world of the Alevis: issues of culture and identity. New York; Istanbul: AVC Publications.

Dressler, Markus. 2007. Alevis. In Encyclopedia of Islam three. Leiden; Boston: Brill.

———. 2013. Writing religion: the making of Turkish Alevi Islam. New York: Oxford University Press.

DuBois, Thomas A. 1996. Native hermeneutics: traditional means of interpreting lyric songs in Northern Europe. Journal of American Folklore 109 (433):235-266.

———. 2006. Lyric, meaning, and audience in the oral tradition of Northern Europe. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

Eberhard, Wolfram. 1955. Minstrel tales from southeastern Turkey, Folklore studies: 5. Berkeley; Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Erdal, Mahmut. 1996. Yine dertli dertli iniliyorsun: barışa semah dönenler. Istanbul: Ant Yayınları.

———. 1999. Bir ozanın kaleminden. Istanbul: Can Yayınları.

Ergun, Sadettin Nüzhet. 1929. XVII’inci asır sazşairlerinden Pir Sultan Abdal. Istanbul: Evkaf Matbaası.

———. 1956. On dokuzuncu asırdanberi Bektaşi-Kızılbaş Alevi şairleri ve nefesleri. 2nd ed. Istanbul: Istanbul Maarif Kitpahanesi.

Foley, John Miles. 1991a. Immanent art: from structure to meaning in traditional oral epic. Bloomington; Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

———. 2002. How to read an oral poem. Urbana; Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

———. 2012. Oral tradition and the Internet. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Gölpınarlı, Abdülbâki, and Pertev Naili Boratav. 1943. Pir Sultan Abdal. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi.

Gül, Muhsin. 1984. Sıdkî Baba: hayatı ve divanından örnekler. Ankara: Muhsin Gül.

Kaya, Doğan. 1998. Sivas’ta âşıklık geleneği. Sivas: S.n.

Koca, Turgut. 1990. Bektaşi nefesleri ve şairleri. Istanbul: Naci Kasım.

Koerbin, Paul. 2011. ‘I am Pir Sultan Abdal’: a hermeneutical study of the self-naming tradition (mahlas) in Turkish Alevi lyric song (deyiş). Unpublished PhD thesis, College of Arts, University of Western Sydney, Sydney. http://handle.uws.edu.au:8081/1959.7/507150

Köprülü, Mehmet Fuad. 1997. Bir kızılbaş şairi: Pir Sultan Abdal. In Kalemlerde Pir Sultan, edited by Ö. Uluçay. Adana: Gözde Yayınevi.

Livni, Eran. 2002. Alevi identity in Turkish historiography. Paper read at 17th Middle East History and Theory Conference, 10-11 May 2002, at University of Chicago.

Özmen, İsmail. 1998. Alevi-Bektaşi şiirleri antolojisi. 5 vols. Ankara: T.C. Kültür Bakanlığı.

Özpolat, Latife, and Hamdullah Erbil. 2006. Melûli divanı ve Aleviliğin tasavvufun Bektaşiliğin tarihçesi. Istanbul: Demos Yayınları.

Rice, Timothy. 1987. Toward the remodeling of ethnomusicology. Ethnomusicology 31 (3).

———. 1994. May it fill your soul: experiencing Bulgarian music. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Ricoeur, Paul. 1998. Hermeneutics and the human sciences. Translated by J. B. Thompson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shankland, David. 2003. The Alevis in Turkey: the emergence of a secular Islamic tradition. London; New York: Routledge.

Yaman, Ali, and Aykan Erdemir. 2006. Alevism-Bektashism: a brief introduction. Translated by A. Erdemir, R. Harmanşah and K. E. Başaran. Istanbul: Cem Foundation.

Endnotes

[i] This thesis is more fully developed in my doctoral research, see Koerbin (2011).

[ii] Personal communication, 2015.

[iii] See Koerbin (2011) for the text and English translation of this deyiş.

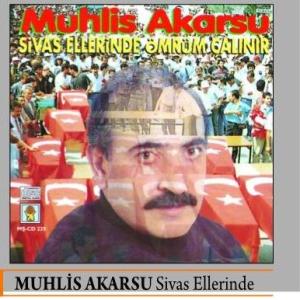

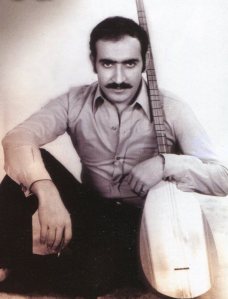

Muhlis Akarsu was prolific in his composition and recordings (in the pre-CD days) and fortunately many have been subsequently released on CD. The more I listen too these recordings, both solo and as part of the Muhabbet series, the more his brilliance is evident. This deyiş is from his last recording prepared shortly before he was killed in Sivas on 2 July 1993. The album was released after the Sivas events with the title Sivas Ellerinda Ömrüm Çalınır which includes the recording of that re-written version of the Pir Sultan Abdal deyiş performed by Arif Sağ (see my previous post). Akarsu’s voice is extraordinarily rich – singing in the deep baritone he favoured from the time of the Muhabbet recordings in the early 1980s – and the songs very strong, mostly his own compositions, including the deyiş that became, after his death, so poignant Yine gönlüm hoş değil (Again my heart is not happy). Akarsu also performs the Turna semahı and Pir Sultan’s Bir güzelin aşığım. Interestingly, Arif Sağ begins his 1993 recording called Direniş (‘Resistance’, recorded only a few days before the Sivas massacre and still only ever released on cassette) with this deyiş although he credits the source as Davut Sulari while the music is credited to Akarsu on his recording.

Muhlis Akarsu was prolific in his composition and recordings (in the pre-CD days) and fortunately many have been subsequently released on CD. The more I listen too these recordings, both solo and as part of the Muhabbet series, the more his brilliance is evident. This deyiş is from his last recording prepared shortly before he was killed in Sivas on 2 July 1993. The album was released after the Sivas events with the title Sivas Ellerinda Ömrüm Çalınır which includes the recording of that re-written version of the Pir Sultan Abdal deyiş performed by Arif Sağ (see my previous post). Akarsu’s voice is extraordinarily rich – singing in the deep baritone he favoured from the time of the Muhabbet recordings in the early 1980s – and the songs very strong, mostly his own compositions, including the deyiş that became, after his death, so poignant Yine gönlüm hoş değil (Again my heart is not happy). Akarsu also performs the Turna semahı and Pir Sultan’s Bir güzelin aşığım. Interestingly, Arif Sağ begins his 1993 recording called Direniş (‘Resistance’, recorded only a few days before the Sivas massacre and still only ever released on cassette) with this deyiş although he credits the source as Davut Sulari while the music is credited to Akarsu on his recording.